Women don't want flowers; we want to be described.

Andrew Garfield once said Emma Stone was like drinking a hot espresso shot in the sun. I can feel her jolt of vitality with just a single sentence.

Don’t call my hair blonde; show me how it flares under noon light or how the baby hairs slip free by 3:00. Compare my smile lines to canyon roads carved out on childhood camping trips. Listen for the moment my voice lowers when I call your name.

Last year, at a paint-and-sip party, couples were assigned to draw each other. I tried capturing the curl of my husband’s hair and his tasteful mustache. The final piece was awful — no sense of scale, definitely not anatomically correct — but cute in its own way.

He took it further: painted a sunflower with bright little petals against a perfect blue sky, the kind of art a third-grader might pin on the fridge. “When I think of you,” he said later when it was just us two, “I think of something wild and bright.” My knees buckled. A year later, I still see that sunflower, a reminder of our 13 years together. Steady, constant, and in full bloom.

The Symbiotic Marriage of Photography & Writing

Photography and writing go hand in hand. Good writing is detailed yet articulate, laced with a tempo that tells a story. A good photograph is a pulse in time that captures how a moment truly felt. Both rely on the visual power of interpretation—showing, not telling.

Take Lisa Sorgini’s work, for instance. She’s one of my favorite photographers right now. Focus on a baby’s hand holding spilled milk, and you get a glimpse into parenthood, right down to the sticky floors that follow. Zoom in, and the setting disappears: it could be a restaurant, the dining room, or the kids’ table at a party. That open door of interpretation makes it an intriguing photo, while the simple subject of a baby’s hand on a half-empty glass stays refreshingly uncomplicated.

This level of mystery is why I prefer to shoot with a telephoto lens: it reveals only part of the story, a tease that sparks an appetite. Nothing baits like a good tease, luring you to the brink before the moment slips away.

Prose works in parallel. Strong writing takes the reader on a journey of rhythmic phrasing, each vowel and consonant a bump or dip in the sentence’s path. It’s about how the words settle in your ear while painting a clear picture. The reader’s grasp should be universal, even as each writer’s style remains distinct. Ultimately, it’s the harmony of meaning and sound that brings it all together.

Deep Observation

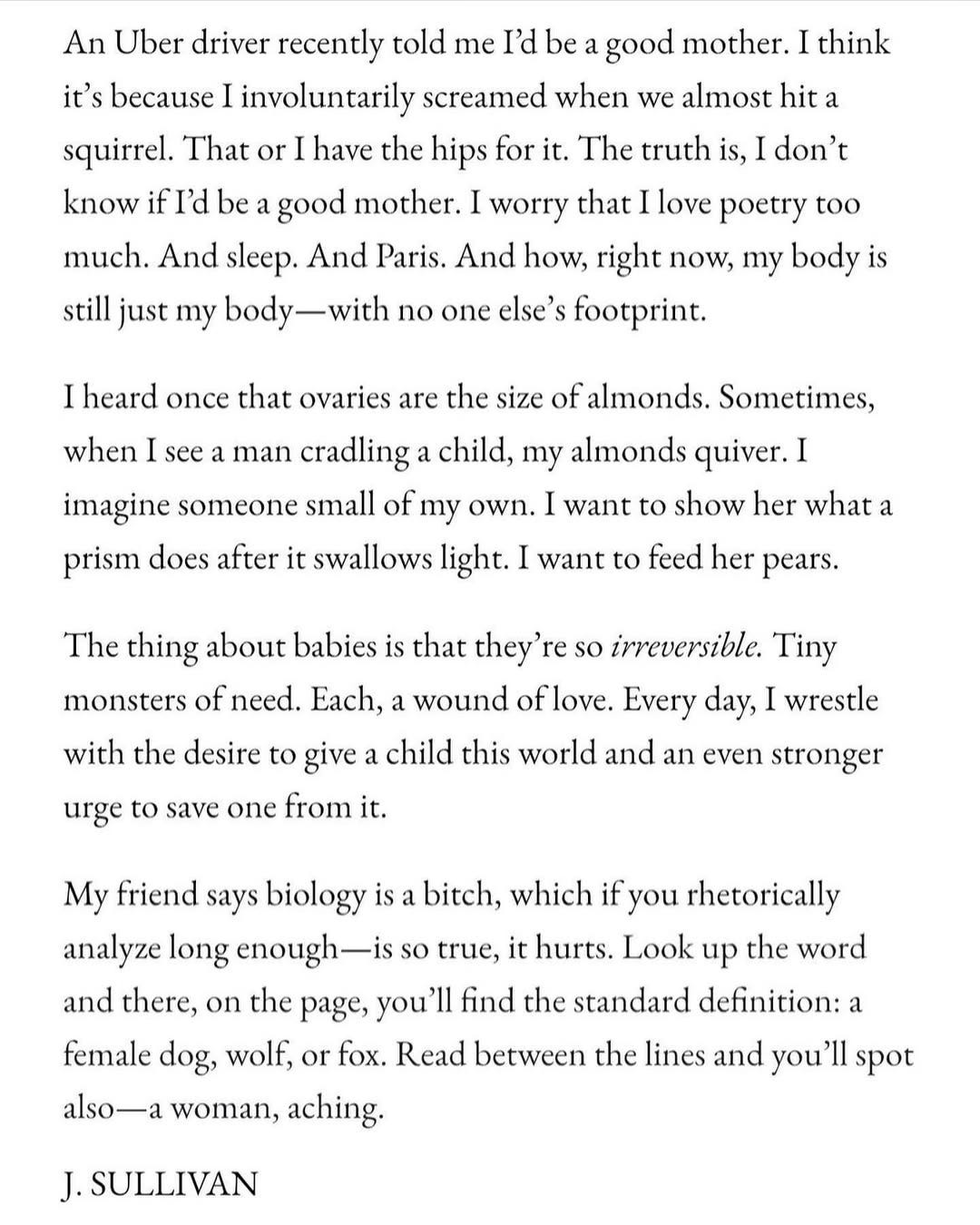

Joy Sullivan is the master of poetry and offbeat one-liners, the blueprint of modern ballads. She hosts online writers’ workshops and non-pompous masterclasses for digging deep into everyone’s psyche; check out her Substack here. In her poem (pictured below), she boldly spins two nuanced topics — fertility and motherhood — around something as ordinary as an almond snack.

“Tension gives your work energy and muscle. Refuse to let your poems be placid. Don’t be afraid to make waves.” - Joy Sullivan

My own creativity hinges on the same kind of keen observation. As both a photographer and editorial narrator, I can’t write anything but non-fiction (hats off to those who do) because I thrive on replaying real moments until I’ve wrung them out. My lust for nostalgia makes it easy to recount the details of years past.

The cabinet handle isn’t just copper, it’s patinaed by a thousand sweaty palms.

Your skin isn’t dry, it’s cracked like desert canyons and salted with age.

The old dog isn’t tired, he’s winded from collecting used socks.

This energy fuels storytelling. Try describing the same object in three to five different ways, each with its own theme or style — comedic once, dramatic another, and brazen the next. Push past the obvious.

Go deep, then deeper.

Starting Is the Hardest Part

I put my heart on the line every day by posting to the internet. Long-form essays on Substack feel spine-breaking to some (or downright cringeworthy), and sharing a new photo on Instagram from a week-old project still makes my stomach churn. Offering a piece of yourself only to be met with indifference can be one of the bleakest parts of creating. Do it anyway.

The most overused sayings are often the truest. It’s obvious, no duh, but repeat this until it sticks: share now, edit later.

Celin’s essay on How to Begin is a near-perfect digest of writing more gripping prose. It covers the basics, like how opening with stark contrasts hooks attention, yet insists you just f*cking start no matter the subject. As John Steinbeck also aid, “abandon the idea that you’re ever going to finish.” Forget the 400 pages you planned; write one page a day and see where it leads. You can’t refine what doesn’t exist yet.

Much of my own essay writing is 80 percent brain vomit; editing for clarity and grammar comes last. Get your ideas down; the messier, the better, and let the typos simmer. Give yourself permission to think with enthusiasm instead of perfection. Write the disturbing and the weird because no one sees your first draft. That chaotic, unguarded moment is liberating. Be specific. Let your first attempt sprawl into chaos.

Sense-making comes later.

Write freely and as rapidly as possible and throw the whole thing on paper. Never correct or rewrite until the whole thing is down. Rewrite in process is usually found to be an excuse for not going on. It also interferes with flow and rhythm which can only come from a kind of unconscious association with the material. - John Stienbeck